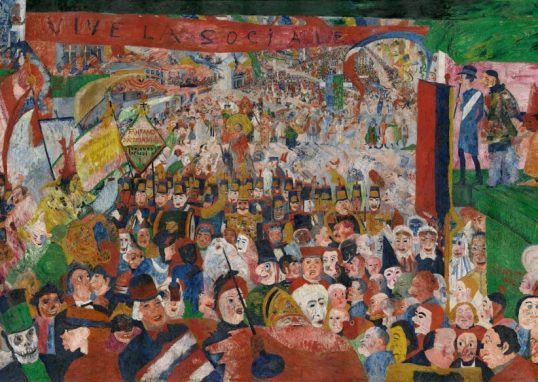

Vergangenen Freitag war meine erste Beerdigung in Schweden. Nicht, dass ich sie selbst durchgeführt habe, nein, ich war „nur“ Beobachter. Unser Nachbar ist am 2. Weihnachtstag verstorben, und als direkter Nachbar wollte ich ihm die letzte Ehre erweisen. Es ist allerdings so eine Sache, auf einer Beerdingung in einem anderen Land zu sein. Vor allem, wenn man niemanden außer den Toten kennt. (Mit seiner Tochter hatte ich dann und wann ein paar Worte gewechselt.) In dem Fall sollte man sich nämlich an all die ungeschriebenen Gesetze und Regeln halten, die jede Kultur für alle solche Gelegenheiten bereithält. Wie leicht ist es da, mit bester Absicht jemanden zu verletzen oder gar zu beleidigen. Ich sprach also vorher mit verschiedenen Pastoren bei Saron, wie eine typische Beerdigung in der schwedischen Kirche abläuft und was ich berücksichtigen, mitbringen, sagen oder wissen müsse. Auch im Team haben wir Fragen wie Kleiderordnung oder die Farbe des Schlipses diskutiert. Und in der Tat: Wenn man diesen Dingen auf den Grund geht, stellt man fest, dass es vielleicht kleine, dafür aber ganz schön viele kleine Unterschiede zwischen den Gepflogenheiten gibt. Insgesamt gesehen, fühlte ich mich wohler, vorbereitet zu sein. Schon lange hatte ich auf eine solche Gelegenheit gewartet, einmal an einer „normalen“ Beerdigung teilzunehmen. Oft bin ich schon auf Göteborger Friedhöfen gewesen und habe mir Gräber angesehen und Grabsteine studiert. Denn der Umgang mit dem Tod ist ein wichtiger Schlüssel zum Verständnis einer Kultur, der Werte und der Sichtweise von Leben und Tod. Nun, der Gottesdienst am Freitag war kurz aber m. E. sehr schön . Die erste Beerdigung in diesem Land liegt nun also hinter mir.

Last Friday I attended for the first time a Swedish funeral. Our neighbor died a few weeks ago and I wanted to pay my last respects to him. Things like a funeral can be tricky as you live in a foreign country. Especially as you don’t know anybody apart from the dead one. (I just have sometimes had a few words with his daughter.) In such a case you need to stick to the unwritten rules and customs each culture provides for certain occasions. But what if you do not know them? Or if you are not sure? How easy is it to hurt or even insult somebody just by breaking a rule you don’t know, although you have best and noble intentions? I remember my CA Field Orientation as I listened to some of my US-American colleagues. They talked about “rules and customs” in Europe and how depressing it must be for Europeans to have so many sets of “regulations” and traditions. At least some of my colleagues experienced it as “depressing” or a “lack of freedom” in Europe. Well, let me explain, it’s not depressing at all. Neither is it a “lack of freedom”. It’s rather a way of communication. It’s an easy way of expressing how much you love, honor, and care. As a Christian, you can be a real witness. You do it without words, but everybody understands. It’s like a language we need to learn as we live in another country. So I talked with some pastors at Saronkyrkan about a typical Swedish funeral and what I need to know, to do, to say, to take along, to consider. In our team we discussed it as well, things like what to wear or the color of the tie. Those things are important and each country is different. Europe doesn’t equal Europe, not at all. A funeral in Italy is very different from Great Britain, and even Sweden and Germany are distinct cultures. I felt better as I prepared myself for the funeral. After all, I had been waiting quite long for an opportunity of attending a memorial service. Many times I have been on different graveyards of Gothenburg, looking at graves and studying grave stones. The way how a culture deals with death is a central key to understanding that particular culture, understanding their way of looking at life and death. Well, it was good last Friday. I liked the service and the way how they did it. In many ways it was good to be there.