The last blog entry was about the journey I have been on – triggered by almost two decades as a foreigner among foreigners. It took me a while to realise that my world view seems to be based on certain assumptions that, firstly, are not really appropriate to our times and, secondly, are lurking unconsciously, i.e. in the shadows. I would like to get to the bottom of these assumptions. In the hope of discovering not only my own, but above all those of our Western way of thinking. To discover what it means to remain salt and light here, today, and tomorrow.

My first consequence since the pandemic has been to slowly but surely withdraw from social media. They have neither depth nor breadth, they are just useless flashes in the pan. Nice to look at perhaps, but not safe. Perhaps the least dangerous thing about it is that you’re wasting a lot of valuable time there. So: let’s get out of here! I’d rather learn something tangible. So books instead of Insta, authors instead of influencers. Works that have described or written history. Authors who really know what they’re talking about, even if you don’t always agree with them. I wanted to immerse myself in fundamental literature. Works that could help me tidy up the cellar. No more instructions for facade painting or front garden gnomes. But where do you start when you consider yourself to be rather ignorant of history, untrained in literature, and philosophically clueless? The best place to start is probably the one that you can actually manage and follow through with. By finding a book that fits into this category, at least to some extent, a book that really interests you, by an author you like. You don’t have to, no, you can’t start with Aristotle in the original, then you’ll just fail. So that one was the one for me:

Jonathan Sacks: “Not in Gods Name: Confronting Religious Violence“

I knew Jonathan Sacks from several articles. I was impressed by his way of thinking. Sacks was a wise, well-read, cosmopolitan and observant Jew. I had already discussed some of his ideas about the role of religion in our time with my team as European Director. I was given a copy of the book directly from the publisher a few years ago and it has been on my shelf ever since. I prefer to read such books in Swedish because I can communicate locally and don’t have to translate important ideas myself. It also develops my historical-philosophical-theological language skills.

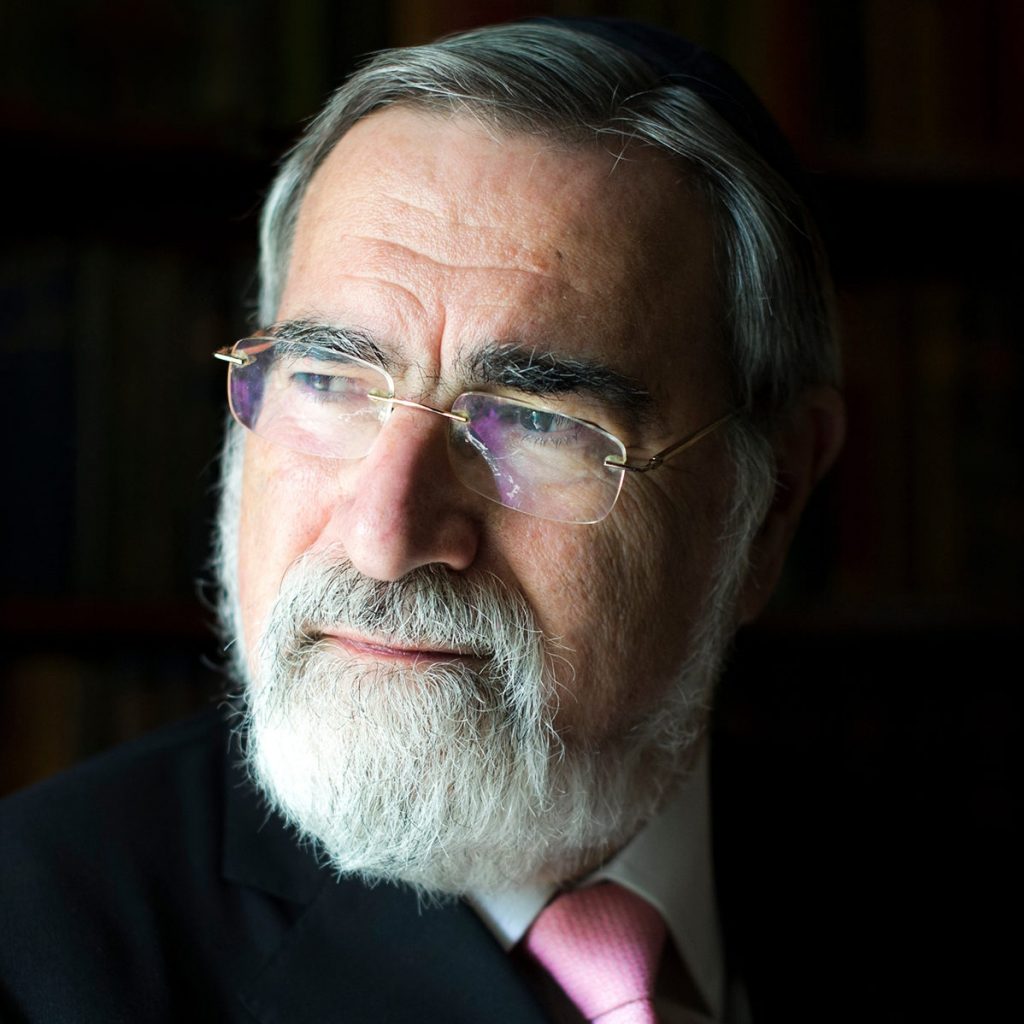

Jonathan Sacks

(1948-2020) was a British philosopher, theologian and author. From 1991 to 2013 he was the British Chief Rabbi.

The original English edition was published in 2015, at a time when religious terror was just becoming an issue in Europe. Sacks looks at ‘evil’ from a number of angles, as well as the strategies people use to deal with it. Of course, he cannot avoid the sibling rivalry between Ishmael and Isaac, and devotes a third of the book to it. In the third and final part, he offers suggestions for dealing with dissenters, issues of power and difficult texts, such as those in the Old Testament.

Sacks writes openly, honestly and self-critically. At no point did I feel that he was bitter or frustrated. On the contrary, his openness and honesty are refreshing despite the gravity of the subject. I learnt a lot from and about history, which is valuable knowledge for me. But I was particularly impressed by the way he interpreted the Old Testament biblical texts with his Jewish tradition and expertise. Familiar stories are suddenly seen in a whole new light, which is fascinating. I wonder why the Church rejected this treasure and instead built its New Testament theology on the foundations of Greek philosophy. This question has been on my mind for some time, but after reading Sack it takes on even more weight. I wonder what churches and congregations would be like today if we had listened more to our Hebrew heritage. How many of my assumptions above that lead us out of the darkness are like strings on a puppet whose end is really pulled by Plato or Aristotle? I don’t know – but I have my suspicions.

Some quotes I like:

All too often in the history of religions, people have invoked the God of life when they have killed, the God of peace when they have made war, the God of love when they have hated, and the God of compassion when they have committed atrocities.

The prophet warns – he does not predict. Tomorrow will be shaped by the choices we make today. For the prophet, time is not the inexorable course of fate, but the response of human freedom to God’s call.

The division of the world into sinners and saints, the redeemed and the damned, is a first step towards the use of violence in the name of God.

Power cannot determine what is right. Nor can victory determine what is true.