Moving abroad, the activism of starting new churches and working with international communities has taught me a lot. More than I ever imagined. But it has also pushed me to my limits, again and again. One of these limits I have reached particularly often: that of my thinking.

Despite my daily life abroad, despite all the teachings and lessons, despite being open to the world and new languages, cultures and people, my thinking somehow remained limited. It took time to realise this. But even when it began to dawn on me, I still didn’t really understood why.

My faith in God, however, which is always greater than my own understanding, helped me. I asked for help. The answer was that book trail. A literary hike along historically stony paths.

The next stage was:

Samuel P. Huntington: “The Clash of Civilisations and the Remaking of World Order“

What I immediately liked about this book was the solid first impression: it feels like you’re holding an important piece of literature in your hand – the colour, the weight, the solid linen cover, the fine paper, the smell – everything makes you want to read and learn. Yes, I’m also reading this book in Swedish. It helps me to communicate here in Sweden.

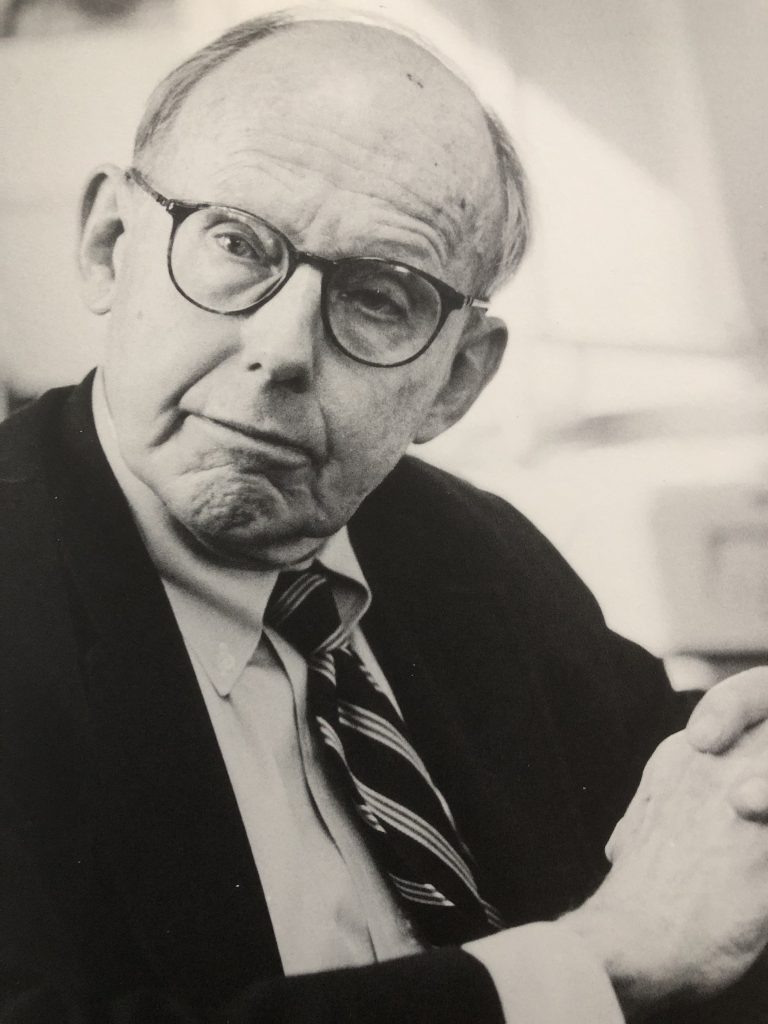

Samuel P. Huntington

Samuel P. Huntington

(1927-2008) was an American political scientist, author and Professor of Strategic Studies at Harvard University. A member of the White House Security Council from 1977-78, Huntington wrote extensively on military ethics and the historical transformation of relations between the military and civilian societies.

Huntington’s work was controversial when it was first published in 1996, and not everyone wanted to believe its uncomfortable assertions. Today, however, publishers in many countries are discovering how right he was and are republishing his book. It is now considered a classic in its field.

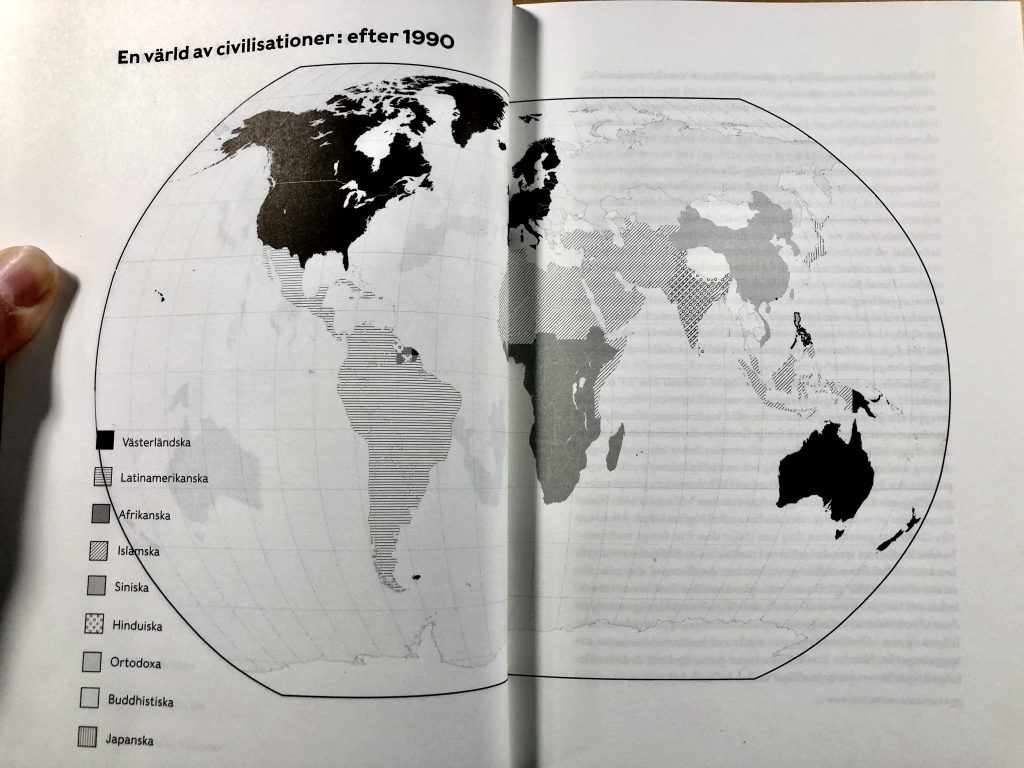

The book attempts to analyse the global situation after the end of the Cold War and to identify possible developments that can be expected in the 21st century. The words ‘clash’ or ‘struggle’ in the title do not automatically refer to armed conflict, but to the clash of different worldviews and value systems – in competition for supremacy. Of course, it cannot be ruled out that this will not be without friction and that in certain circumstances weapons will be used, but this is not really Huntington’s starting point. He explains the civilisations he has identified in the world, what has shaped them historically and how they relate to each other.

In particular, he explores the question of whether, sooner or later, the whole world will tend to be and think in Western terms. An assumption that was not uncommon in the 1990s, when McDonalds or IKEA suddenly spread throughout the former Eastern Bloc, as I well remember. And lo and behold, unconsciously I also somehow assumed that this would happen – that the whole world would eventually become like we are today, because we are so great, and of course everyone wants to be as great as we are. Subconsciously, even international missionary work since the 18th century has not always been so easy to distinguish from the westernisation of the world. That’s an important self-knowledge I take away from the book.

Huntington reminds us that colonisation was anything but civilised. It was a militarily enforced exploitation of other countries that were simply unable to defend themselves. The West may want to forget this, but others remember it very well. This may be the main reason why the rest of the world sometimes reacts with resentment to Western demands that ‘human rights’ be respected. People may not be against human rights per se. But the fact that the West first brutalises other countries and then hypocritically insists on respecting its own (Christian?) ‘values’ does not always go down well. Huntington quotes, for example, the Moroccan-Islamic women’s rights activist Fatima Mernissi, who is praised by the West. Coincidentally, I found one of her most important books, ‘Islam and Democracy‘, in a second-hand bookshop. What she has to say about Western democracies doesn’t sound very complimentary. According to Mernissi, the world is traumatised by colonial terror because Western individualism is the source of all problems.

Huntington also introduces the Persian insult gharbzadegi. It means something like Western poisoning or Euromania. In other parts of the world, people place much more value on community, faith and morality. But because of secularisation, this is exactly what is hard to find in the West. Combined with the traumas of history, this will lead to a growing anti-Western attitude, Huntington argued in 1996.

For me, these are really relevant insights. For if I come along today as a German or a Swede and claim to preach the one and only truth, even in faith, I may be chipping away at the same notch of cultural superiority. I would quickly become a hypocrite – closing more doors than I could ever open again. So it is important to proceed wisely and with caution.

Incidentally, Huntington has been criticised for oversimplifying the complexity of a global world. I think that’s a pretty stupid comment and I would claim the opposite. Huntington has helped me to see my own naivety in a world that is much more complicated than I could see with my Western background and glasses.

Einige Zitate und Einsichten, die mir gefallen

The term ‘la guerra fría’ (the cold war) was coined by the Spanish in the 13th century to describe their conflictual relationship with Muslims.

The West conquered the world – not through superior ideas, values or religion (to which few members of other civilisations converted), but through its superiority in the use of organised violence. This is a fact that the West often forgets – non-Westerners never forget.

At a fundamental level, our world is becoming more modern and less westernised.

The most devastating contractions in the future are likely to result from a mixture of Western arrogance, Islamic intolerance and Chinese assertiveness.

The West’s fundamental problem is not Islamic fundamentalism. It is Islam, another civilisation whose people are convinced of their cultural superiority and obsessed with their powerlessness. The problem of Islam is not the CIA or the Pentagon, but the West, another civilisation whose people are convinced that their culture is universal and who believe that their superior, albeit weakened, power gives them a mandate to spread their culture throughout the world. These are the main components of the conflict between Islam and the West.