I wasn’t sure whether to put this book on my public reading list about my literary walk. The book itself wasn’t my first choice; it’s not a Christian piece, nor is it particularly common in Europe. I only added it to my library because it is in the same series as Huntington’s ‘Civilisations’. Combined with the same high quality of the copy, this gave me hope of an equally high literary value. The subtitle ‘History for decision-makers’ tipped the balance in favour of purchase. My years as European Director were like a little taster course in international thinking and leadership. But when it became clear that I wanted to be wise rather than statesmanlike, and that meant HE had to get greater and I had to get smaller, I hung up my cosmopolitan hat. But the experience and the questions remained. Today I know that big decisions are only as good as their preparation, and the more they influence the future, the deeper and more firmly they must be rooted in history. That’s why the title ‘Thinking in Time’ appealed to me.

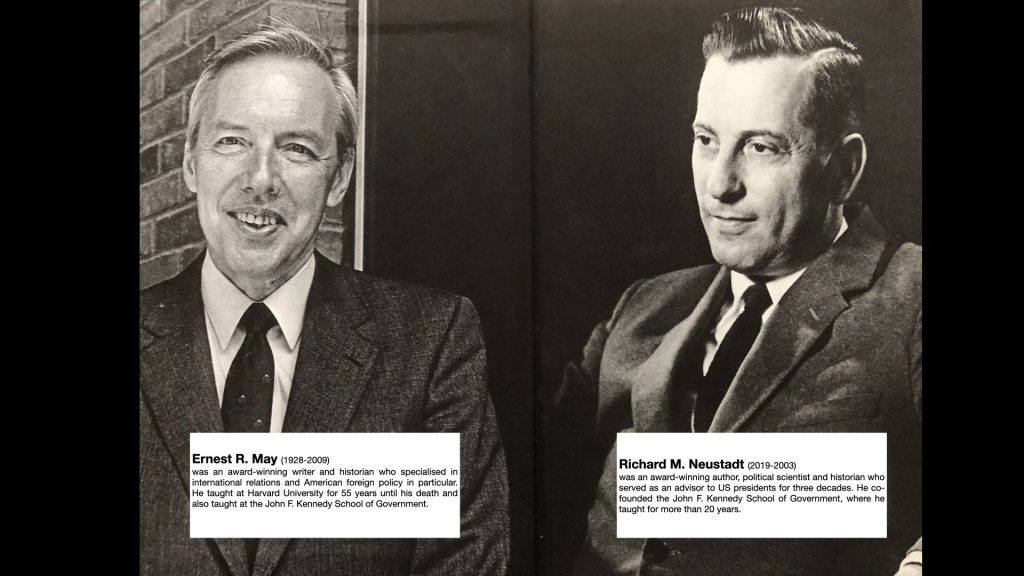

The Authors

Ernest R. May (1928-2009) was an award-winning writer and historian who specialised in international relations and American foreign policy in particular. He taught at Harvard University for 55 years until his death and also taught at the John F. Kennedy School of Government.

Richard M. Neustadt (2019-2003) was an award-winning author, political scientist and historian who served as an advisor to US presidents for three decades. He co-founded the John F. Kennedy School of Government, where he taught for more than 20 years.

In their book, the two authors present numerous cases in which American presidents had to make important and far-reaching decisions. Using transcripts and other reliable documents, they analyse how and why these decisions were ultimately made. They give the reader some simple tools to make good and sensible decisions when it counts. The first is: Stop! Look! Listen! Don’t just carry on, get a picture of the situation. The second is to identify as accurately as possible what is known, what is unclear and what is suspected. Only those who can distinguish between these three will be aware of the potential risks of the decision. The third is to compare the current situation with historically comparable situations, distinguishing between similarities and differences. All three sets must be applied constantly and repeatedly. And this is where it usually fails, as many (but not all!) cases in this book show.

All too often, for example, assumptions are confused with facts. Or people see the similarities but not the differences. Because people don’t take the time to stop, look and listen. The result is often decisions with disastrous consequences that could have been avoided relatively easily. The Vietnam War is a case in point.

For me, this book is instructive simply because you get historically documented insights into formerly top-secret meetings and processes that would normally remain hidden from you. More importantly, it vividly confirms my belief that people all too often make unwise, not to say stupid, decisions because they don’t take the time to think things through. A lot of things are driven by the subconscious, and then you wonder why things went wrong. Even at the highest political level. There is a lot of human behaviour there too. For me, the book is a signpost that I am moving in the right direction on my reading journey.