The first stages of this journey to the centre of the mind may have been a little rough, but now things are getting stormy. Horst-Eberhard Richter really stirs the pot. In his analysis “The God Complex” (1979) he observes that something is not quite right with young people. He refers, for example, to Wir Kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo (The English translation was published in 1981 as “H. Autobiography of a Child Prostitute and Heroin Addict“, translated by Susanne Flatauer), which became a prominent example of the sharp rise in drug use in the second half of the 20th century. Richter sees in this, as in other alternative youth cultures of the 1970s, a pattern of young people’s discontent, a protest by adolescents against the absurdity of Western social development. Even then, Richter wanted to get to the bottom of the hidden causes, just as I do today, and set about his research with his experience and expertise as a doctor, psychiatrist and psychoanalyst. His diagnosis was an unhappy awakening. But the book is so topical that it was reprinted in 2005.

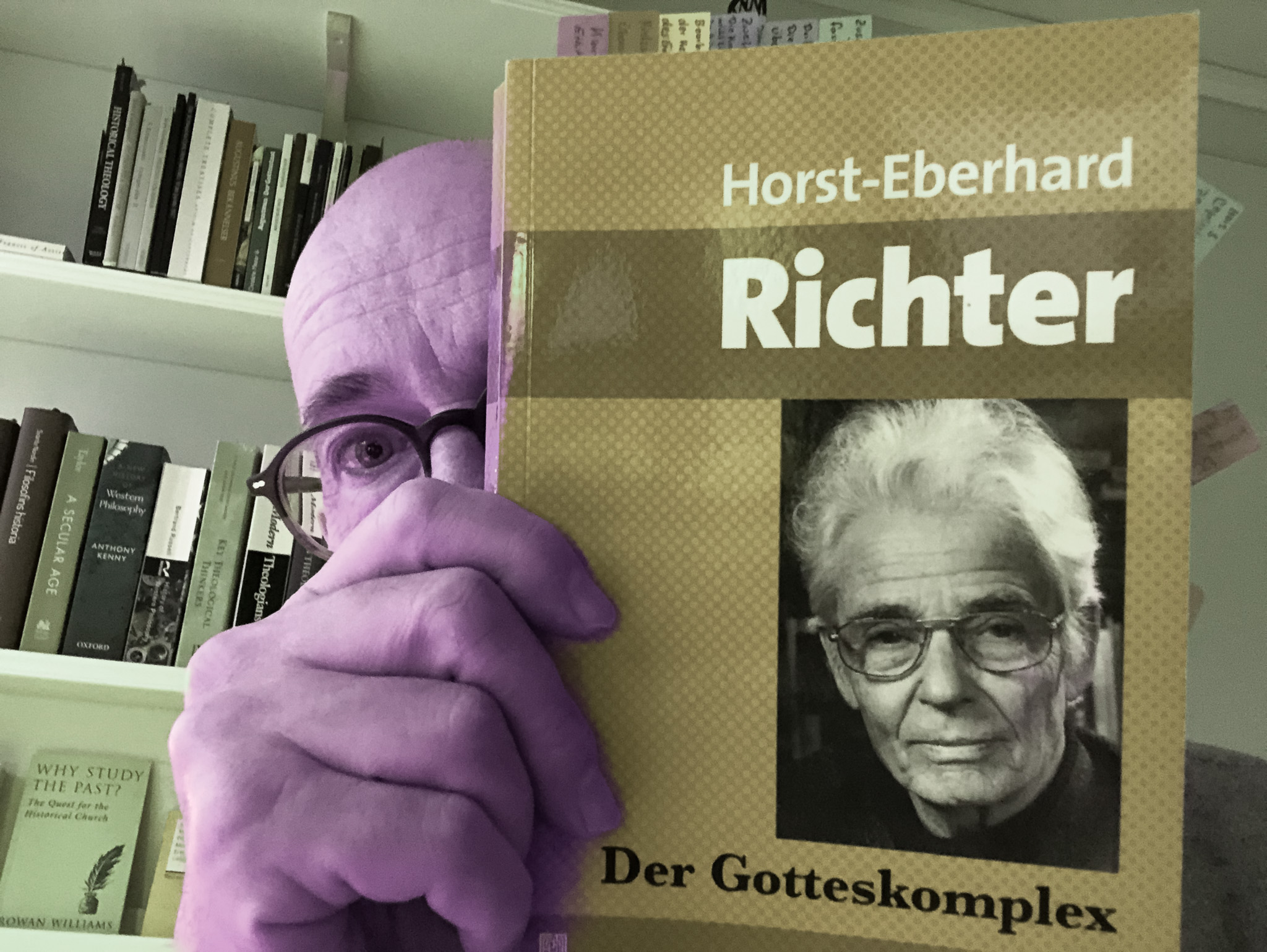

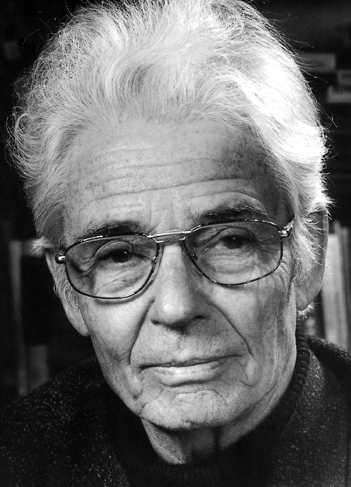

Horst-Eberhard Richter

(1923-2011)

Medical doctor, specialist in neurology and psychiatry. Psychoanalyst and professor of psychosomatics. Social philosopher and activist in the German peace movement.

Richter compares the state of Western society with the typical psychological behaviour of a permanently defenceless child, for example because it has become parentless too early: in order to compensate for the growing insecurity, it slips into an illusionary parental figure itself, so that it does not feel constantly defenceless and at the mercy of an unreliable life situation. But according to Richter, this is only an infantile illusion fuelled by unresolved fears – in reality the child experiences a constant, convulsive self-overload.

The West, on the other hand, behaves in exactly the same way: its orphanhood began with the Enlightenment, when people said goodbye to God as the father of humanity. After the loss of divine protection, the individual ego became the guarantor of modern security. The grandiose self-assurance of the ego had replaced the lost security of the parental figure and was now responsible for an exorbitant overestimation of one’s own importance and possibilities. The individual ego was transformed into the image of God, and the fear of being abandoned by God became the fear of losing absolute self-confidence and intellectual control over one’s environment.

However, the long-praised Enlightenment liberation of medieval man into modernity was basically nothing more than a neurotic escape from narcissistic powerlessness into an illusion of narcissistic omnipotence: behind the facades of our seemingly so imposing Western civilisations, we find that infantile megalomania again, nourished by deep, unresolved fears. However, the fear of admitting to the infantile dependency that has been suppressed since the Middle Ages is fatally greater than the fear of perishing with an objectively suicidal megalomania. Richter calls this curse of a collective powerlessness-omnipotence complex the “God complex“.

With impressive precision, Richter moves through the writers of the Enlightenment and their many ideas: Reason, freedom and the pursuit of knowledge were highly valued. However, Richter shows that this era not only provided positive impulses, but also laid the foundations for the God complex. The focus on rationality and progress created an attitude that placed man at the centre – often as the almighty “ruler” of the world. Enlightenment thinkers such as René Descartes emphasised thought as the highest expression of human existence, leading to a world view in which not only the human being was the thinking subject, but everything else – nature, society, even other people – could be dominated and controlled. The separation of mind and matter reinforced the idea that man, as a rational being, was above “irrational” nature. This attitude was later reinforced by technological progress and science. Francis Bacon, for example, saw nature as something to be “unravelled” and “mastered”. Man became the “master of creation”. Richter shows how this optimism about progress led to a dangerous hubris: When everything is scientifically explainable and technologically feasible, limits are overlooked.

Incidentally, Richter is particularly critical of the sharp distinction between the rational and the emotional, because it has led to the glorification of the male sex and the dumbing down of the female sex, to the devaluation, oppression and ridicule of women by the ever-glorious, strong, rationally thinking male human.

Richter also questions the Enlightenment understanding of “reason”: what happens when reason is elevated to absolute authority? He warns against an overvaluation of reason that can displace empathy and humility. The Enlightenment not only led to freedom and democracy, it also laid the foundations for totalitarianism and technocratic power. Belief in God was replaced by a belief in the “perfect order” and the rationality of all things, which later found extreme expression in the bureaucracy of modern states or in totalitarian ideologies.

We encounter the power of love much less often than the power over love.

Horst-Eberhard Richter

But this delusion of omnipotence, which still dominates our thinking at all levels today, in no way eliminates the God complex. The child remains defenceless, exposed, powerless – despite all the illusions. “Most of us are so deeply desperate inside that we have to take refuge in superficial surrogate satisfactions,” Richter analyses and explains Max Scheler’s law of surrogate formation. Young people take drugs in public or join sects or “left-wing alternative groups”, as he calls them. But he warns against pointing an accusing finger at them:

“What [the addicts] live out uninhibitedly and in an extreme way … the majority of well-adjusted citizens do only in a more orderly, patient and moderate way: namely, self-anaesthesia to cover up a desolate lack of security and an existential feeling of being lost.”

45 years after the first publication, we suspect that Richter is not wrong in his analyses – on the contrary. Contemporary phenomena such as consumerism, drug abuse, pornos, excessive or compulsive travel and much more are fully in line with Scheler’s law of surrogate formation. But even phenomena such as Trump, Brexit or the general polarisation of our societies are basically just desperate, increasingly aggressive attempts to regain control. Richter’s proposed solution is a much-needed recognition of both our own and society’s mechanisms of repression. He calls it the “sympathy principle”, by which he means sympathy for the representatives of social suffering – i.e. drug addicts, cults or those “left-wing coloured alternative groups”. Today we could add climate change activists or mentally unhealthy young people to the list, because they are all like a litmus test for social oppression. They need to be taken seriously and listened to in order to reintegrate them into our society. If we don’t succeed in doing this, if we keep pointing the finger at them instead, or, even worse, if we try to lock them away as villains, the repression will only increase and we will end up producing, albeit unconsciously, more of the “witches and devils” whose inquisitorial persecution we are constantly calling for.

Basically, Richter sees the medieval image of God as one of the main causes of the socio-psychological characteristics of modern Western civilisation. As a non-theologian, he makes no suggestions for improvement. But I’d assume, today it would be necessary to emphasise the incarnate, compassionate, self-sacrificing God who is particularly interested in the marginalised and has no interest at all in wordly political power.

For me, reading this book was like turning the key to a new room with windows that offer completely new perspectives. And even more bookshelves.