Instead of the usual Christmas kitsch with aspic and gravy, and in keeping with the literary journey I’m on, I’d rather give you a portrait of the author, sociologist, historian, philosopher and theologian who, in my opinion, has described better than anyone else what the incarnation of heaven actually means in the West of the 20th century.

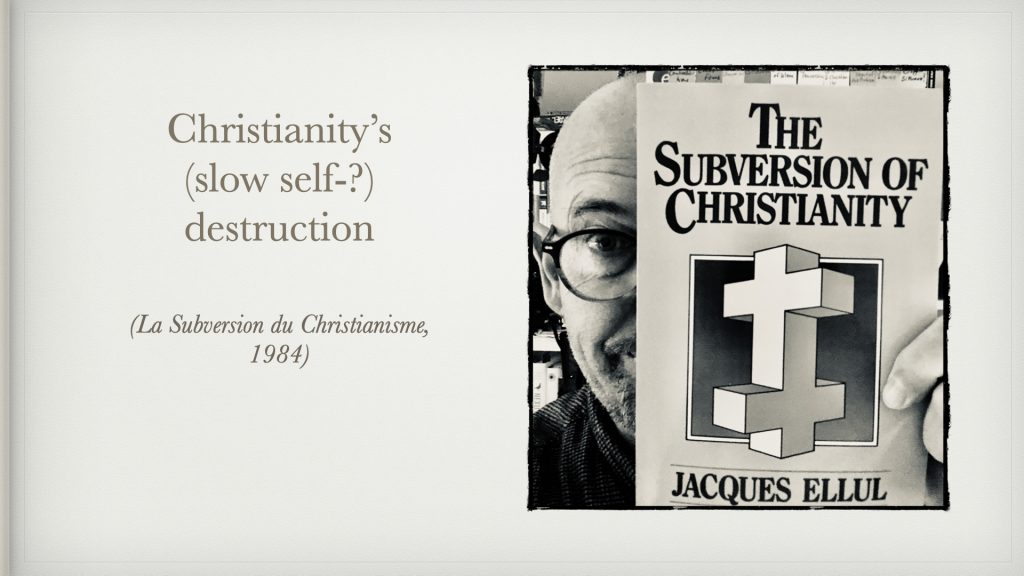

At the end of my theological studies, I had to do an extended intercultural internship, i.e. in another country, in another language. We moved to Scotland and became part of a congregation that was completely different to any church or congregation I had ever known. Deeply theological, but every service was a celebration with a buffet, food, drink, music and wine. People sat at tables and discussed the sermon, sometimes directly with the preacher, who took extra breaks just for that purpose. People met in pubs for “pub theology”, discussing what reconciliation means today with anyone who wanted to, over a pint and a cigar. And much more of the same. Pastor Wesley, who was also my mentor during the internship, took me aside at the beginning and said: “Marcus, if you really want to learn how to think and how to do church differently today, then you should read these books!” He gave me a reading list to read during the internship and to discuss with him and his team. At the top of the list was Jacques Ellul: The Subversion of Christianity.

In this book, Ellul takes stock of the Christian faith and examines the practices of the Church throughout history. His verdict is unflattering, to say the least. The Christian faith, in his view originally a radical movement for love, freedom and justice, has been distorted and lost its original purpose.

Throughout his book, Ellul regularly uses the terms “the subversion of Christianity” and “the perversion of Christianity” as synonyms. This is because the church itself has become part of the structures it was once supposed to question. Instead, it has opted for historical compromises, making deals with power and politics.

Ellul criticises the church for using power to justify oppression and violence, and calls for a return to the subversive love and freedom that Jesus proclaimed. So that was my first encounter with Ellul in 2005.

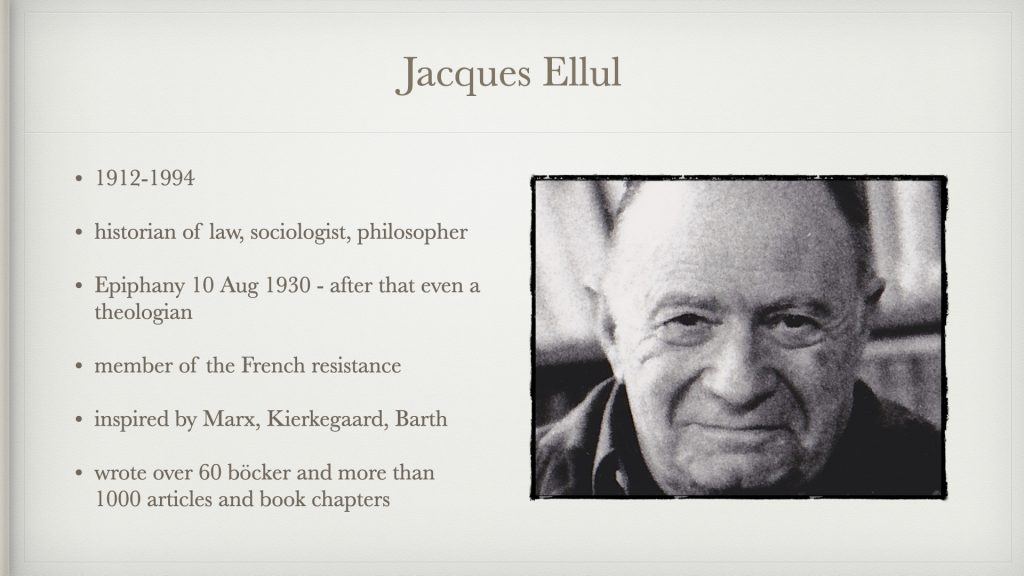

But who was Jacques Ellul?

He said of himself that it was pure chance that he was born in Bordeaux on 6 January 1912, but that it was his choice to stay there. He studied the history of law and sociology and obtained a doctorate in Roman law (a subject that recurs in his writings).

Earlier in his life he had been associated with the Catholic Church, but after a vision of God in August 1930, which he never wanted to describe in detail but which must have been a kind of conversion experience for him, he became a member of the French Reformed Church.

He realised that there were Christians who put all their energy into evangelism and the Bible, and others who put all their energy into political activism. He himself could do little with either. And maybe that’s an indication that he doesn’t really fit into any mould. He was often looking for something different, a more adequate solution, something better than what already existed.

When Germany occupied France, he joined the Resistance. He is absolutely for resistance, but just as absolutely against violence. Ellul helped Jews escape from France to Switzerland, sometimes risking his own life. He even studied theology during the war, but never finished.

Marx was a person who inspired him, although he considered his analyses to be very outdated. Theologically, he was inspired by Kierkegaard and Barth and by the “infinite qualitative difference between time and eternity”, which may explain his search for more and his dissatisfaction with the secular church, which he felt was often too easily satisfied with worldly pleasures.

He wrote more than 60 books and over 1000 articles and book chapters. He passed into eternity on 19 May 1994 after a long illness.

This is one of his most famous works, which in my brief overview will only serve as an example of his way of thinking.

The Technological Society is a profound critique of the way technology has come to dominate modern society and human life. Ellul describes technology as an autonomous system driven by efficiency and productivity that dehumanises society and restricts individual freedom. Technology increasingly influences the way we think, act and interact with each other. Ellul warns that technological society is in danger of losing its humanity if technology is not questioned and controlled.

This is only a very brief summary of the book. But what is interesting is that he sees technology as a power. A power that dominates human beings.

Just as mammon is a power that Jesus warns against loud and clear. The state is also a power that only wants to rule over people. In his book The Subversion of Christianity there is a chapter called “Political Perversion” where he says that political power is an idol – and we are not supposed to serve idols. This is why Ellul is sometimes called a “Christian anarchist”.

Propaganda is another power he warns against. Propaganda is just another tool to control people. Propaganda often goes hand in hand with great ideologies that tell people what to do and what not to do. He sees these forces as spiritual realities to which we are exposed and which must be resisted. This is why it is so important for him that the church, the followers of Jesus, do not do what everyone else does. To be completely different is vital for the church, says Ellul.

Ellul is therefore very critical of all-encompassing explanatory models and theoretical systems. All explanatory models must be constantly questioned. Otherwise there is a danger that they will take on a quasi-religious status and, in the worst case, people will start fighting for them. He is extremely critical of the Church as most people know it. He says that the Church has been de-Christianised, and that this began as early as the 3rd century, when the Church transformed the imperial cult into a Christian cult, when the Church adopted beliefs, pagan myths and customs that were completely alien to the Good News. But the Church did not then and does not now recognise that these choices destroyed the revelation of God in Christ. The Church is to be the antithesis of the world – and NOT part of the world’s destructive power system.

The church is to preach and embody the “wholly other”. The church is not even to accomplish anything by itself – the church is only to make visible in the world what has already been accomplished in the world.

Aware of the importance of creation, Ellul became one of France’s first environmentalists. He questioned many of the destructive mechanisms that drive economic growth at the expense of the earth’s resources. In 1981, in the preface to the first Swedish edition of his book “Presence in the Modern World“, he wrote very self-critically that he should have considered the mechanisms of environmental destruction when he wrote the book in 1948 (!). I find it fascinating that in the same book Ellul reminds us of the sin of the collective – something we have completely forgotten in our purely individualistic version of the Gospel. Because we are forced to participate in a sinful system, and each of us bears the consequences of the mistakes of others. Therefore, according to Ellul, it is not enough to focus on individual salvation and individual moral virtues, because we are no longer dealing with individual sins, but with the sin of humanity. We too are responsible for the sins of previous generations – going back to the fall of man.

And with these thoughts of Ellul, which are often rooted in the wars of the 20th century, he is basically on the same path as we are today with regard to environmental destruction, where I too would like to stress the importance of collective repentance.

Perhaps I like him too much to see his flaws. Perhaps the only thing I see as a weakness is that he is so far from the norm in his conclusions and challenges that he is not always understood by ordinary churchgoers. After all, Kierkegaard and Barth are his philosophical and theological parents. And he tries to apply their ideas to the twentieth century. This may be a little too much of the “wholly other” to understand. On the other hand, he is also seen as the man who foresaw (almost) everything. This means that his ideas may only now, in the twenty-first century, be coming to fruition.

For example, here are two books that have been published (or republished) relatively recently in Sweden: Against Violence and Presence in the Modern World.

Here is an article from the latest issue of “Nod” magazine comparing Ellul to Reinhold Niebuhr.

I would really love to see Ellul inspire many more pastors around the world to rethink their practices, as he inspired Pastor Wesley in Scotland. Then church would be less about religion and more about something else entirely. After all, we are supposed to make the Wholly Other present in this world.

With that in mind: Merry Christmas 2024!